Khecari mudra is a yogic practice praised in Sanskrit yoga texts as one of the most potent practices of them all. Yet today, Khecari mudra is, for the most part, passed on in a simplified manner. Despite the renaissance of yoga, those who practice Khecari in its full form remain rare. But that is starting to change.

In this article, I will give a full description of both the common Khechari and the advanced practice. I will tell you about how I started practising the preliminary version of Khecari mudra and how I, almost twenty years down the road, was inspired to take on the full practice as described in the ancient yoga manuals. Read on to learn how you can achieve it yourself and how it can benefit your yoga practice.

The most powerful mudra

In early yoga, the asanas we associate with yoga today were absent. Instead, practices included meditation, breath retention (pranayama) and mudras. A mudra is a yogic energy seal or a physical manipulation that influences subtle energy currents. There are plenty of mudras, some that involve the whole body, and little ones that just include finger placements or eye position.

A story that I heard my teacher Swami Janakananda tell over and over again during my training was when he asked his guru which mudra is the most important one. Janakanada’s teacher was Swami Satyananda Saraswati, founder of the Bihar School of Yoga. He was an expert on advanced yoga practices and author of many books on the topic.

Janakananda expected his master to say, Maha Mudra. After all, the Sanskrit word maha means the greatest. It is one of those big mudras, and it has a pronounced energy raising effect. Instead, to Janakanda’s surprise, Satyananda said that Khecari mudra is the most important.

The spacewalking seal

The Sanskrit word Khecari means “to move in space”. You will find different spellings of it because there are several ways to represent Sanskrit letters with Latin characters.

The British researcher and Sanskrit expert, James Mallinson calls Khecari mudra “the spacewalking seal”. The name suggests that practitioners of this mudra experience an intoxicating sensation of flying through the inner space.

One who practices this mudra is known as a Khecara.

Khecari mudra in the tradition of Swami Satyananda

The way I learned Khecari mudra from Swami Janakananda, and he in turn from Satyananda was to fold the tongue backwards and rest the tip of the tongue against the soft part of the palate. That is how nearly all present-day yoga instructors teach Khecari, and it is challenging enough for most beginners. When I first tried it, it felt awkward, and I was unable to do it because my tongue would not reach back far enough.

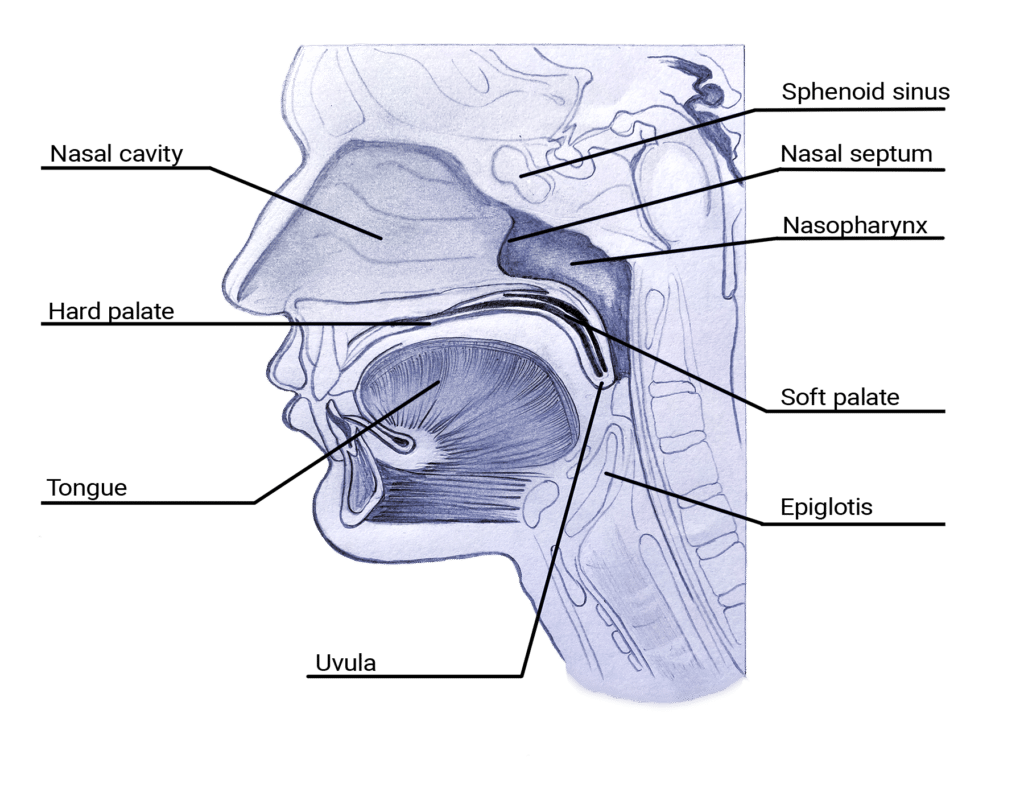

If you place your tongue right behind the teeth in your upper jaw, you can feel that the mucus membrane that coats the inside of your mouth sits on the bone of the skull, and is hard. Slide the tongue a little further back, and you feel an upward slope as you get in behind the bone structure that holds the teeth. After the slope, the palate levels out and becomes soft. The soft palate stretches out back in the direction of the throat and ends with the uvula.

Though the most common instruction is to rest the tongue on the soft palate some teachers will encourage you to try to reach to the uvula.

The raja yoga and the hatha yoga form of Khecari

The reason most people can’t get their tongues very far back is the frenulum linguæ. It is the membrane under the tongue that fixes it to the floor of the mouth. In my case, the frenulum linguæ was a little tight. But notwithstanding, I soon started liking having my tongue in this mudra. It became a natural part of the exercises where it is recommended, in particular Ujjayi pranayama. I was comfortable with it, and it made my Ujjayi breath smoother. Within a couple of years of daily practice, my frenulum had on its own gotten long enough that I could just reach the soft palate.

Swami Satyananda calls this easy form of Khecari the “raja yoga form” in the 1973 edition of his book Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. He describes the full form of the mudra vaguely, and he calls it “the hatha yoga” form.

Satyananda claims that the folded tongue stimulates pressure points in the back of the palate. He writes that the mudra has extensive health benefits and that the saliva produced during Khecari can remove the feeling of hunger and thirst. Satyananda also writes that this mudra can awaken the kundalini shakti.

As for myself, though I found the raja yoga form of the mudra pleasant, I never could feel any significant impact on my mental state or my energy. But I knew many other methods that had an apparent influence. That Khecari would be the most potent mudra was not coherent with my own experience. But I accepted that I might not be subtle enough to perceive its benefits.

Bjarke’s spontaneous initiation into Khecari

Bjarke was one of Swami Janakananda’s early teacher students. By the time I did my training at the beginning of the 2000’s he was already an accomplished teacher and leader of a retreat centre in Bergen, Norway. In the early seventies, when he was still in high school, Bjarke had a spontaneous initiation into Khecari mudra.

He had learnt Transcendental Meditation, TM, and after a year of regular practice, he had a milestone experience. During one sitting, the meditation completely overtook him. He did not in any way take part in that which unfolded; he was but a witness. It was like his body stiffened to the point that he was unable to move, his breath stopped altogether, and his tongue moved by itself backwards and rested on the soft palate. At the same time, an inner space expanded around and beyond him.

He contacted his TM teacher for an explanation to this deep but at the same time frightening experience. The teacher said it was just an experience and that Bjarke should let it come, and go. This is an essential meditative attitude and a good reply. Still, when he became a student of Swami Janakanada, Bjarke found that not only Khecari but also the other experiences from his spontaneous initiation were taken into account by the yogic tradition.

Bjarke says that many yogic practices, including Khecari, aim at recreating natural responses and processes triggered by deep meditation. As such, they can themselves to some degree set off the states by which they are caused. A sort of yogic reverse engineering.

Spontaneous Shambhavi

Spontaneous experience of Khechari mudra is not that uncommon. Bjarke is one of two people that I know in person who have had this experience. The internet gives a superb possibility to connect people with particular interests. Because of that, I know of more.

A similar process that other yoga teachers and I have observed is spontaneous Shambhavi mudra. You do Shambhavi mudra by fixing your gaze in the point between the eyebrows. This naturally occurs for many people when they are in deep relaxation, without them even being aware of it. I see it happening especially to my yoga students during Nadi Shodan pranayama. With eyes half-open, their gaze will move upwards and inwards.

Khecari mudra as described in the Sanskrit yoga texts

Khechari mudra is one of the oldest yoga practices to have been written down. In its easy version, it is mentioned already in Buddhist Pali texts, though in an unfavourable way. Remember, Buddha didn’t like yoga.

In early hatha yoga texts, Khecari is critical. There is even a whole text dedicated to it, the Khecari Vidya. Khecari Vidya is an influential text, and many of its verses are echoed in later writings, for example, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.

In 2007, when James Malinsson wrote his critical edition of the Khecari Vidya he was doing ethnological fieldwork at the same time in India. He tracked down khecaras and interviewed them about their practice. Despite being well connected in the sadhu milieu, he only managed to find six individuals practicing full Khecari.

In the ancient Sanskrit texts, the description of Khecari goes beyond the simple contemporary version. Instead of letting the tip of the tongue rest on the soft palate, we are instructed to pull the tongue further back. Then it becomes possible to reach behind the uvula and insert it into the nasopharynx, for most people, an unimaginable feat at first glance.

Swatmarama, author of the 14th century Sanskrit text Hatha Yoga Pradipika, recommends achieving Khecari by gradually cutting off the frenulum linguae using a sharp blade. He writes that the yogi should cut away a hair’s width every seven days. Then he should rub a mixture of salt and turmeric into the wound to prevent it from closing or getting infected. According to Swatmarama, it will take six months to sever the frenulum linguae entirely.

For many years I thought this sounded far out.

What you don’t know, you fear

Based on the cutting of the frenulum, I have often heard the full Khecari presented as a dubious fringe practice. To spice up the story, it was suggested that some yogis split their tongues in half to be able to close both nostrils from the inside. At this point in the story, there came a word of warning; one who was bold enough to close the nostrils from the inside might panic. Such a panic attack could cause death from suffocation if the tongue wasn’t reversed to a normal position in due time.

The truth is that it is easy to bring your tongue to a normal position. The risk of getting stuck is pure fiction. As for the splitting, I am yet to come across a yogi with a split tongue. I can’t recall having found references to such a practice in any source text either. Cutting the frenulum is a rather basic intervention, whereas to split the tongue strikes me as a much more complicated and hazardous thing to do. With modern hygiene and medical practices, it is possible, though. Since early 2000, tongue splitting has become popular within the body modification community.

My first contact with advanced Khecari

I had practised the basic version of Khecari for more than ten years when I first came in contact with someone who practised the big one. In an online conversation with the Russian yoga teacher and writer, Ilya Zhuravlev, he described how he had crisscrossed India for years looking for a teacher who could initiate him into old school hatha yoga, including full Khecari. He finally encountered a teacher who had been himself taught by a grandson of the famous 19th-century master Lahiri Mahashaya. The teacher requested full Khecari before more profound initiations.

Ilya wrote that Lahiri had considered the frenulum cutting prescribed by the Hatha Yoga Pradipika a “deterioration of yogic knowledge”. Instead, he had prescribed stretching. Ilya claimed that one could achieve Khecari within a period of months to years by a simple daily tongue stretching routine.

Having been turned off by the chirurgical approach, stretching resonated with me. Going further with Khecari all of a sudden appeared as an eluding possibility.

I did some more research and stumbled upon a comment written about Khecari that made an impression on me. A woman wrote that she had learnt full Khecari from an Indian yogi decades ago in her youth. Out of everything she learned from this yogi, this was the practice she had kept and practised throughout her life. She cherished it and was thankful for having taken the time to learn it.

The anatomy of Khecari mudra

Yogani, a present-day partisan of the full Khecari, has defined four stages of this mudra. According to his terminology, the first stage is when the tongue touches the soft palate. This is the Khechari nearly all present-day yogis practice and that Swami Satyananda called the raja yoga form. There happens to be a Sanskrit name for this stage too. The 17th-century yoga text Gheranda Samhita calls it Nabho mudra. A distinction is thus made in this text between the first stage and the later ones that are referred to as Khecari.

The second stage is when the tongue can penetrate the nasopharynx and rest above the palate. The nasopharynx is the hollow extension of the mouth situated over the palate. This is where the mouth meets the nose.

Early on in the second stage, your tongue can slip back into the mouth. At this point, the mudra is likely to feel awkward and clumsy. But once you master the second stage and your tongue can rest above the hard palate, the mudra is comfortable to perform. Your tongue stays in place almost by itself.

At the beginning of the second stage, many practitioners need to push the tongue into place using their fingers. But with prolonged work to loosen the frenulum, it becomes possible to get the tongue in place without aid.

Stage three and four

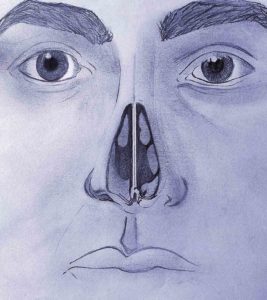

As the second step evolves and the restraint of the frenulum is reduced through cutting or stretching, the tongue will reach further and further forward. Soon you can feel the sharp wall dividing the two nostrils with the tip of your tongue. This is the nasal septum. The nasal septum is the bone and cartilage in the nose that separates the nasal cavity into two nostrils.

Because of the nasal septum, the tongue can’t at this point move further forwards. Instead, it will very slowly start climbing up along the nasal septum. When the tongue reaches this far, you can feel the interior openings of the nostrils on either side.

When your tongue reaches so far that it can touch the ceiling of the nasopharynx above the nasal septum, then you have reached stage three. Here your tongue will touch the Sella Turcica, a bone whose most interior parts hold the sphenoid sinus and the pituitary gland. Placing the tongue here closes a primary pranic circuit.

Stage four involves twisting your tongue and inserting it into your nostrils, one at a time.

Forrest Knutson is a Kriya Yoga teacher in the tradition of Panchanan Bhattacharya. He shares his knowledge on his Youtube channel. According to him, stage four is not better than stage three. It is different and stimulates different energy currents. He says that master Lahiri Mahasaya practised both stage three and four.

As an anecdote Khecaras that are proficient in stage four can close their nostrils completely using their tongue, but only one at a time. Hence they can do the alternate breath without using their fingers.

The astrophysicist that became an explorer of inner space

Yogi Maheshwar is the author of the ebook Khecari Mudra – when the divine goddess takes off in inner space. He is sensitive to yogic practice, and when I read the fantastic account of his experiences, I was intrigued. I owe him my gratitude for being the igniting spark that made me start working towards Khecari.

Yogi Maheshwar or Mahe as he also calls himself, describes how he started yoga and how, after some years of practice, his tongue would spontaneously roll backwards, as had happened to Bjarke. But in this case, the response was continuous, occurring outside of yoga practice and so intense that the stretch in the frenulum became painful.

He ended up being convinced that this reaction was a sign that his tongue wanted to reach deep into Khecari. Thus he decided to remove his frenulum. Before doing it himself with the sterilised blade he had already purchased, he went to the hospital to see what help they could offer. His determination helped to convince the stomatologist, who scheduled an operation.

The operation removed the frenulum linguae, and the road was thus cleared for the tongue. Mahe got very tangible results from his new practice, and he also gave it a serious go. When he first ventured beyond the primary stage with his tongue, he stayed in Khecari for ten hours.

Psychedelic insomnia

In the evening following this first ambitious exploration, he was unable to sleep due to psychedelic like experiences. Still, after this night of psychedelic insomnia, he felt great. And in addition, he did not feel the urge to eat for some ten days. His body was content with its natural energetic state, and though he tried eating on several occasions, his body refused any food. At the same time, he continued to sleep little but was still charged with energy.

I recommend anyone interested in this mudra to read Yogi Maheshwars inspiring and well-written ebook. He has written the book like a scientific paper with precise references to his many sources. He has published an English translation, but if you are very proficient in French, I recommend the original because it is such a pleasure to read.

You can download Yogi Maheshwars ebook for free from his website >>>

I met Yogi Maheshwar in Paris a couple of months after I read his book. With a long beard and dreadlocks, he looks like he just teleported from an Indian ashram. What makes Mahe even more of an intriguing person is that he is an astrophysicist. At the time of our meeting, he was working as a researcher for the CNRS. That is the French equal to NASA.

The nectar of immortality

In hatha yoga mythology, it is said that there is a cosmic fluid, amrit. This is the nectar of immortality that drips from the head down through the body and is consumed in manipura chakra. It is said that during deep meditation, yogis feel amrit as a sweet taste in the mouth. Khecari mudra stimulates its flow.

There seems to be something about this elixir, and many practitioners claim to have felt it. My wife recently came back from a three-month yoga retreat in Sweden. The retreat participants practised Swami Satyananda’s Kriya Yoga in sessions that would last for hours. After such sessions, my wife says that she frequently felt a sweet taste in her mouth. A taste she never feels otherwise.

At the same time, let’s remember that there is plenty of fluid produced in the nasopharynx and the nose that has nothing to do with yoga practice.

The cosmic poison

According to mythology, there is also supposed to be a kind of cosmic poison produced if the yogi is impure. Yogi Maheshwar writes in his book that he felt a metallic taste in his mouth during the night following his first experience with Khecari. That taste reminded him of a taste felt during an LSD trip in his youth. He speculates that this taste might have caused him some digestive problems after his spontaneous fast had ended.

A yoga student I once taught stage one Khecari said the mudra made her feel an awful taste in the mouth. It appeared soon after placing the tongue against the palate and disappeared if she withdrew the tongue. She consulted a recent edition of Swami Satyananda’s Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha and found a recommendation to discontinue the practice if such a taste is felt.

A better approach that is advised in some scriptures is to spit out the foul-tasting saliva instead of swallowing it. Eventually, the taste will change and first become neutral and then agreeable.

Contraindications and precautions relating to Khecari mudra

The second edition (from 1973) of Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha is the oldest one I have. In it, Swami Satyananda writes that the hatha yoga form of Khecari should only be learnt under the guidance of an expert.

The editors changed this passage in the 1996 revision. That is the case with many other entries in this book. Now the hatha yoga version is not recommended at all “as the effects make it unsuitable for interaction with the outside world”.

Forrest Knutsson says that the only counter-indications he can see for practising full Khecari are headaches and “severe kundalini symptoms”.

How to achieve Khecari

Yogi Maheshwar is one of only two individuals I know of who has removed the frenulum in one go and had it done by a public health care provider. Yogani, the teacher who has defined the stages of Khecari, recommends using sterilised sharp plyers for better precision. But otherwise, his method resembles the one Swatmarama describes in the Hatha Yoga Pradipika.

Some people suggest using a practice called Talabya Kriya. The idea is to extend your tongue out of the mouth and use your lower jaw teeth to grind the frenulum down. Though some claim to have had success using this method, to me, it seems inefficient.

Dohan kriya, tongue milking, is another practise that yogis use to make their tongues longer so that it can reach further. The principle is to gently and repeatedly pull the blood in the tongue towards its tip using your fingers in a milking motion. In Khecari Vidya it is also described as to how you can tie a cloth around the tongue and pull it to prolong it.

There is no need to overdo it

I think there is no need to become fascinated with the length of the tongue to enjoy Khecari.

Forrest Knutsson says he feels compassion for adepts who deform their tongues in pursuit of an extreme Khecari practice. He says that in his lineage, the goal is that the tongue reaches the sphenoid sinus, stage three, according to Yogani terminology. Forrest’s recommended way of getting there is stretching. He suggests stretching until the frenulum is slightly sore and then wait until it has healed before repeating. If you overdo it, he says, it will take days to recover, and it will take a longer time. And time you will certainly need, because this stretching is a marathon. Most of us should expect it to take years to reach stage three.

How I worked towards Khecari myself

When I decided to explore the advanced stages of Khecari, I decided to go for stretching. I simply pushed my tongue backwards with my fingers for five minutes twice daily. In my case, I would say that my frenulum was slowly torn rather than made more supple.

I reached the second stage after about ten months of daily stretching. It took me many more months to be able to keep my tongue in the nasopharynx for meditation. In the beginning, there was a lot of salivae and a general feeling of discomfort. As my tongue started getting comfortable, it took me even longer to get used to doing Ujjayi pranayama with the tongue in its new position. I found it more challenging to produce the whispering Ujjayi sound and to keep a slow rhythm.

But Khechari grew on me and thanks to a bit of patience it soon enough became pleasurable, and the Ujjayi breath fell into place.

Benefits of advanced Khecari in Kriya Yoga

Full Khecari mudra is a defining feature of the Kriya Yoga practice of Lahiri Mahasaya. Forrest Knutsson says that Khecari runs parallel to the Kriya Yoga programme.

According to his tradition, one of its benefits is that it draws attention, energy, and the sense of self, back towards the brain. Furthermore, he says, it engenders a profound healing bliss, and in so doing helps the Kriya effect of cleaning the chakras.

The notion that this mudra brings about bliss is a recurring attribute I have come across in my research. This bliss is also something I have started to experience more and more myself. It is a sort of energetic bliss that sweeps in waves through the whole body. It resembles the energetic sensations I sometimes get when I guide a group of concentrated participants through deep meditation.

Satyananda instructed only the preliminary Khecari for his Kriya Yoga system. Since Satyananda praises this mudra as the most important one, I find it odd he never went all the way in teaching it. Based on what I have gathered looking into this practice and based on my own results, shifting from stage one to stage-three Khecari is a definite improvement to kundalini practices.

A giant leap for mankind

Yogani teaches advanced yoga online through text lessons and an online forum on his website Advanced Yoga Practices. He is enthusiastic about Khecari calling it “A giant leap for mankind”.

“A centimeter or two above the roof of our mouth is located one of the most ecstatically sensitive organs in our whole body. It can be reached relatively easily with our tongue. It is located on the back edge of our nasal septum, and when the nervous system is purified enough through advanced yoga practices, our tongue will roll back and go up into the cavity of our nasal pharynx to find the sensitive edge of our septum. When this happens, it is like a master switch is closed in our nervous system, and all of our advanced yoga practices and experiences begin to function on a much higher level. When kechari is entered naturally, we come on to the fast track of yoga. It is the major league of yoga, if you will.”

– Yogani

Spontaneous vs willed Khechari

This inspiring passage comes from online lesson 108 that Yogani has dedicated to the Khecari Mudra. Yogani seems to be saying that it is when there is a spontaneous urge for the tongue to by itself reach backwards that Khecari shines. The importance of this spontaneousness frequently comes up in comments on his forum. Should I interpret that as Khechari being an efficient practice primarily if it happens by itself as it did for Bjarke and Yogi Maheshwar?

I have heard of a yogi who had his frenulum removed, just like Yogi Maheshwar. But for a long time, Khecari did not give him any significant results, though he did it to perfection. I asked Forrest what he thought about this matter.

Forrest says that he thinks Khechari should come together in practice as a part of a whole, as mentioned in Yogani’s lesson. Yet, he says that to expect that every individual will experience the lifting of the tongue automatically is erroneous. According to him, there is a central tenant in yoga which should never be ignored: that good works will bring good results. A good strategy is neither to force your way nor to wait for it all to just fall in place by itself.

My experience of Khechari so far

For my part, I did not expect miracles. That was another reason cutting did not appeal to me. I expected a practice to grow slowly. At the beginning of stage two, I felt no benefit compared to stage one. It took me a long time to get used to having my tongue in the nasopharynx.

Gradually I started valuing this mudra more and more. Three years into the practice, as I am approaching stage three, I consider it one of the most potent methods I know. It has an immediate impact on my energetic and mental state and adds depth to other practices.

The statement that Khecari mudra is the most important one no longer feels foreign to me.

Should You do Khecari and how should You go about?

If you are a practitioner of Nabho mudra, the preliminary Khecari or baby Khecari as some call it, you might wonder if it is worth the trouble of achieving full Khecari. I think Khecari is worthwhile. After twenty years of yoga practice, I am happy to have discovered another deep-reaching tool. I think you would be too.

As with other advanced yoga practices, good judgement, a gradual approach and practicing within your limits cut the risk of any possible adverse effects.

As for how to get there, I would recommend stretching.

Special thanks to Mona Bessaa for the anatomical artwork in this article.